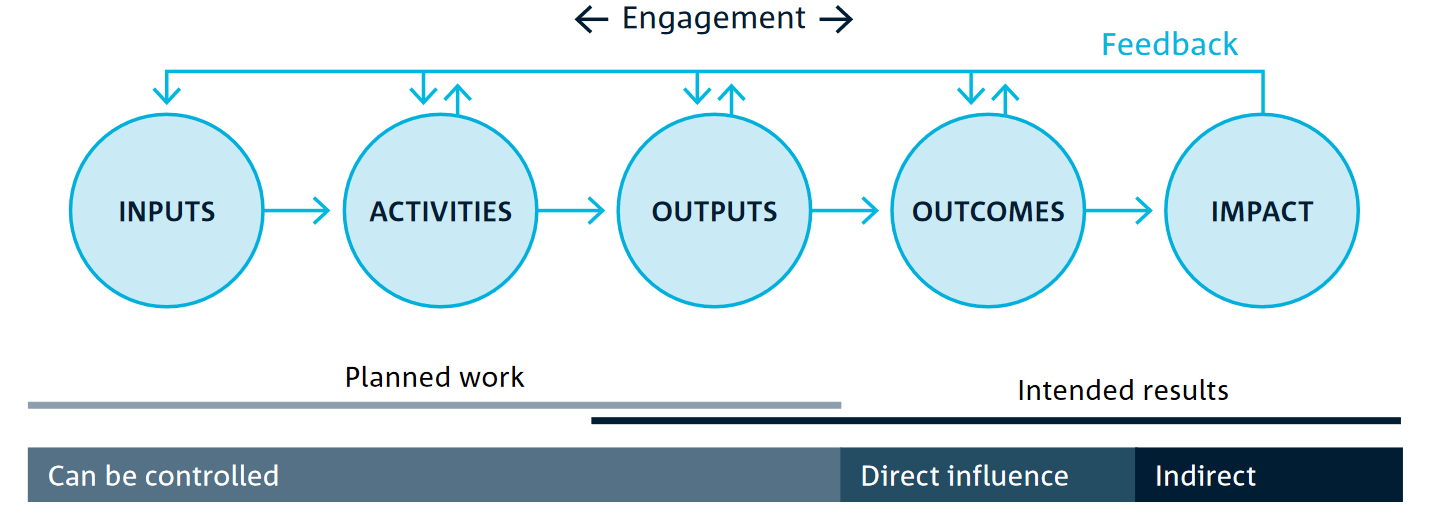

The question of how to value cultural institutions or activities has been central in the cultural debate for quite some time. In the 1980s the emphasis was on the economic impact of the arts (e.g. Myerscough 19881), later on, their social impact (e.g. Matarasso 19972). At present, there is a tendency to consider the value of culture as something quite more complex and holistic, particularly the social aspects, which cannot be reduced to a monetary form. As explained by Throsby (20013), cultural value can, in turn, be deconstructed into aesthetic, spiritual, social, historic, symbolic and education values, each of which contributes to a different facet of the overall value subsisting in a cultural object, institution or experience (Bollo 20134).

Therefore, measuring economic and social impacts of the cultural and creative sectors means to capture and make visible the benefits generated by an economic investment (sustained whether by individuals, communities, businesses, governments) but it also means to highlight the benefits of the investment in terms of time and human capital and to show the secondary and collateral effects generated by cultural activities. It means to provide CCIs with an instrument to evaluate the cost and production efficiency of the resources used for the development of their own cultural activities and then to fix their planning process and apply improvements and corrective strategies, if due. In other words, it means to provide valuable knowledge and support to the audience development and new business and management models.

UNESCO has stated that “One of the challenges of a culturally-sensitive development agenda is the ability to measure its impact. The attempt to quantify the specific contribution of a ‘culturally-appropriate’ development policy, as opposed to one that does not take culture into consideration, is unavoidably complex”. Impact is in fact a quite complex concept and it implies several different challenges while measuring it.

First, there is a question of isolation of impact from effects. This means that, as everyone is surrounded by a diversity of signals and messages, it is almost impossible to isolate which message was the one making an impact (for instance in the educational field, if we would like to assess changes in worldviews). It is hard to isolate and attribute different influences. For instance, did my worldview change because I attended a single event? Most likely no, but an event could have triggered conversations, which would lead to seeking more information, which might be confirmed or challenged. At the end of the day, I might have changed my perspective, but it is hard to say how it happened. At the same time, cultural institutions and organisations often have a desire to be able to understand their relevance or measure their impact precisely from this angle. Have we made a difference? This is increasingly hard to demonstrate.

Secondly, when we discuss impact measurement, it is often an activity that is very much oriented towards specific decision-makers. If cultural institutions are under strong pressure from funders to demonstrate the impact of their work, then the funders also often have specific indicators through which they will evaluate success. At the same time, if a drive to understand impact comes from within the organisation as a need for feedback, validation and input for future planning and programming, then the organisation is much more able to choose its own indicators.

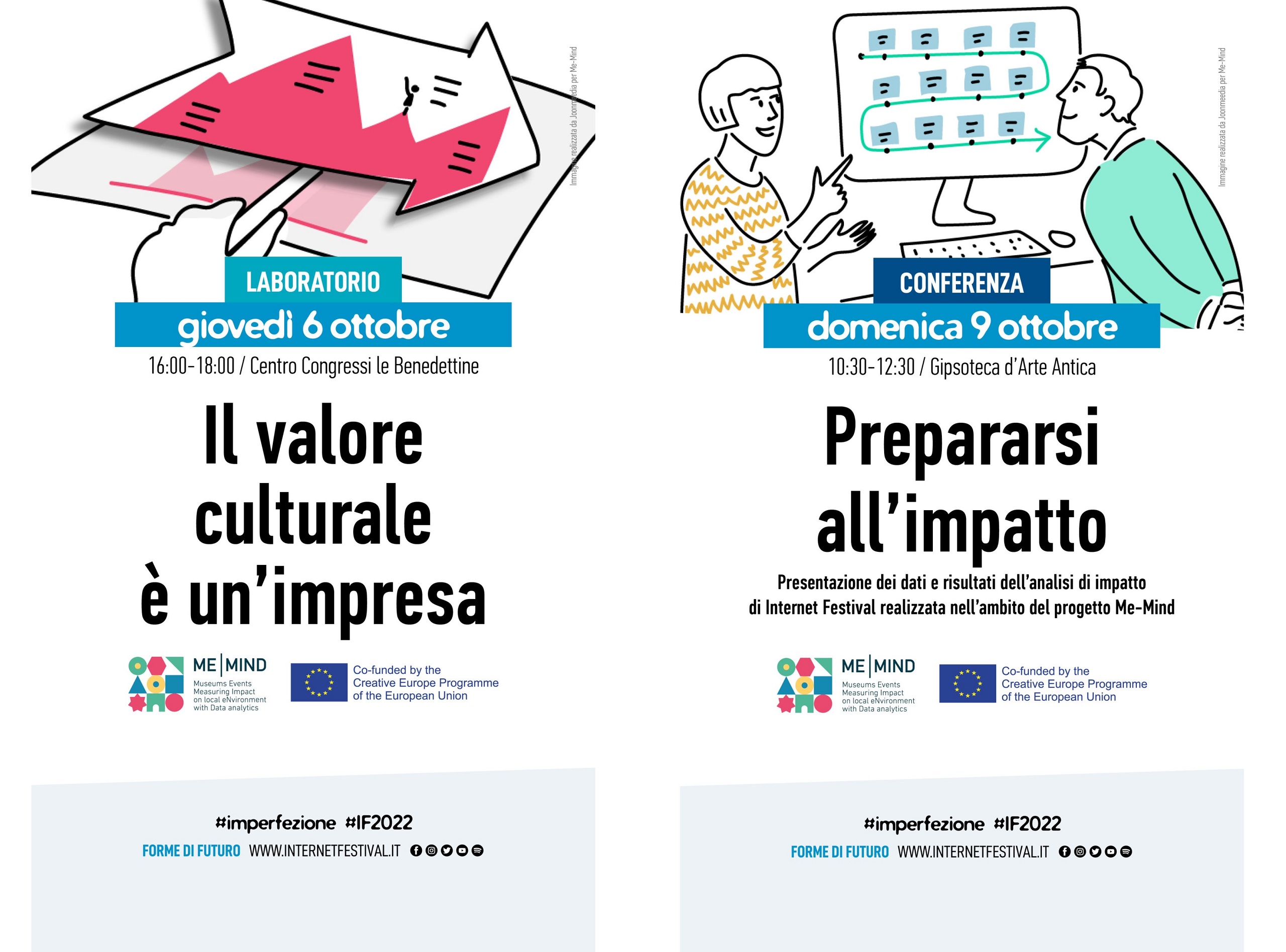

Thirdly, often when discussing measurements, there is a challenge in differentiating between efforts, input, output and income. This last point has been discussed quite often also in a research context. Both cultural organisations and research institutions are doing impactful work, which is communicated through multiple challenges and which has the potential to change the world as much as it has the potential to be forgotten in a drawer. Australia’s National Science Agency CSIRO has worked with impact assessment and evaluation and has developed a model that has been widely used and adapted elsewhere. The model distinguishes between inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes and impact. As such, the model critiques the approach where only activities or outputs are measured to understand the impact of the activities. Yet, CSIRO proposes this model for planning purposes allowing the research actors to plan for impact through considering activities and outputs (CSIRO 2020).

The Utah Museum has used a similar model, where they distinguish between short-term, intermediate and long-term outcomes, seeing the last ones as impacts. At the same time, their impact indicators are relatively vague, looking for increased well-being, intercultural competence, continued learning and engagement as well as strengthened intercultural relationships. This takes us to the idea that while envisioning impacts at the end of a scale where inputs, activities and outputs presumably lead to impact, the challenge then becomes around the question of operationalisation. If we see ourselves having an impact through life-long learning or stronger relations, what should we measure to be able to argue that such impact exists?

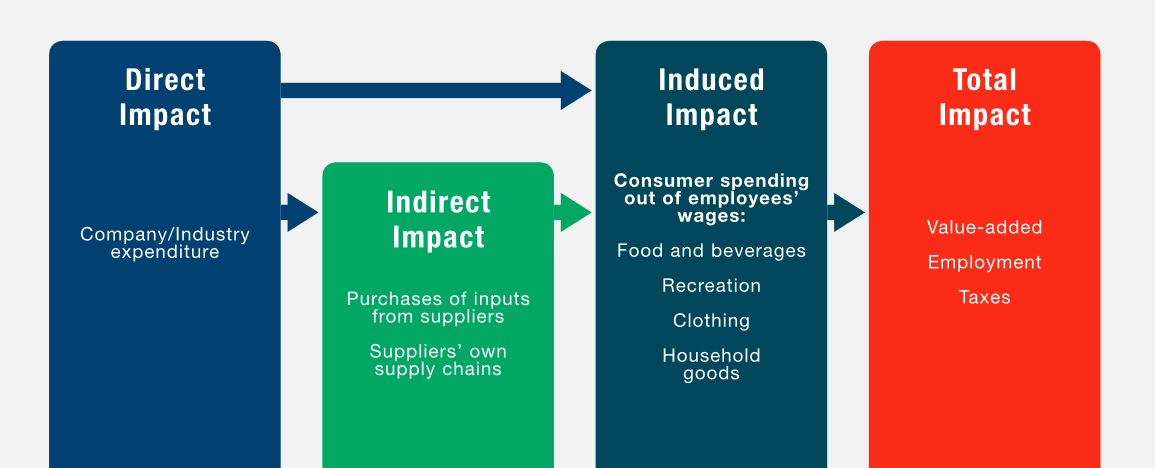

Another report demonstrating the diversity of indicators was put together by the American museums, the figure below shows that museums have a direct impact through spending their budgets with other sectors, indirect impact as their supply chain provides work and economic value to their partners. Additionally, consumer spending and taxes add up to a complex network of impacts showcasing museums as important financial players.

The main goal of the Me-Mind project is to provide a methodology for Cultural and Creative Industries (CCIs) for making better business decisions based on the measurement and analysis of their activities’ impact, combining several data sources, exploiting Data Science and ICT technologies to enrich the amount of information available and use Data Visualisation to support the decision making process. Specifically, it aims to facilitate CCIs to have more efficient impact measurement and to make benefits more evident towards public administrations, potential public and private sponsors as well as the general audience.

________________________________________________

- Myerscough, J. (1988). The Economic Importance of the Arts on Merseyside, London: Policy Studies Institute.

- Matarasso, F. (1997). Use or Ornament? The Social Impact of Participation in the Arts, Comedia, Stroud.

- Throsby, D. (2001), Economics and Culture, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Bollo, A. (2013). Report 3. Measuring Museum Impacts. The Learning Museum Network Project. https://online.ibc.regione.emilia-romagna.it/I/libri/pdf/LEM3rd-report-measuring-museum-impacts.pdf