How technology and data can be blended into the culture industry to increase the value of the sector.

A few weeks ago, I was rediscovering my hometown of Barcelona, through an insightful tour about the origins of the Roman city, understood through the remains of their ancient architecture still visible in the old town.Today we can understand our ancestors thanks to archaeologists who have the ability to understand how they were living during this age. This understanding is possible because of methods that transform cultural and architectural realities into data that can show us how people lived. Their traditions, fears, military strategies, celebrations and even their affinity for luxury crockery; transforming stones and objects into data that has the ability to paint an anthropological picture of the past.

Nowadays, we have the opportunity to track our society and leave a legacy for new generations, and use this information to better face the challenges we have as humans in a limited planet and complex societies.

For some of us, data and technology are two terms that are all too often associated with neoliberalism and technocapitalism. However, much like all human inventions, it depends not on the tool itself, but on the intentions of the user and the resulting consequences. As Domestic Data Streamers we strongly believe in the potential of blending data and technology with cultural institutions and organizations. The main purpose is to transform the practices of these social and cultural agencies so that they match the velocity with which this society is changing.

The fact that cultural industries and movements can use data doesn’t need to affect their core values. What we propose is an acceleration and improvement in the efficiency with which they listen to society, generating insights that reduce the distance between policy leaders and citizens.

Since 2018 we have toured the same exhibition in Barcelona, Beirut and Hong Kong, that communicates with visitors and collects data about their opinions and visions on the topic of design. This exhibition was called Design Does, and it aimed to open a dialogue about the limits of design in modern society.

We exhibited 14 pieces to discuss the role of design in the challenges that we all shared. All the visitors were anonymously identified with a card that was used to answer all the questions, and all this data was allocated in our database in order to analyze patterns and different opinions of the visitors.

For example, we recreated conversations on one of the most important dating applications, Tinder, to show visitors how many uses this application has. These ranged from seducing and winning over voters during the US presidential elections in 2016, to publicly outing homosexuals in Russia, and even trading illegal drugs. We shared a question: Do digital apps help us to relate to one another in different ways or are they standardising our relationships?

Another installation was a recreation of an automatic gun designed, produced and sold by Samsung to South Korea and installed in the border between the two Koreas. This gun uses Artificial Intelligence to automatically decide if someone is an enemy to the country or not. In this case we shared the question about who is responsible for an innocent death, the designer or the politician that bought this machine?

We also asked about social networks and how these platforms were perceived by the visitors. We proposed the question; Who knows you best, Google and Facebook or your family? One of the most relevant results was that 75% of teenagers believed that their families know them better than Google and Facebook. However, this is the generation with the greatest exposure to the data industry, and this industry knows more than their families about their hobbies, fears, relationships and the personal challenges they face in one of the most important phases of life.

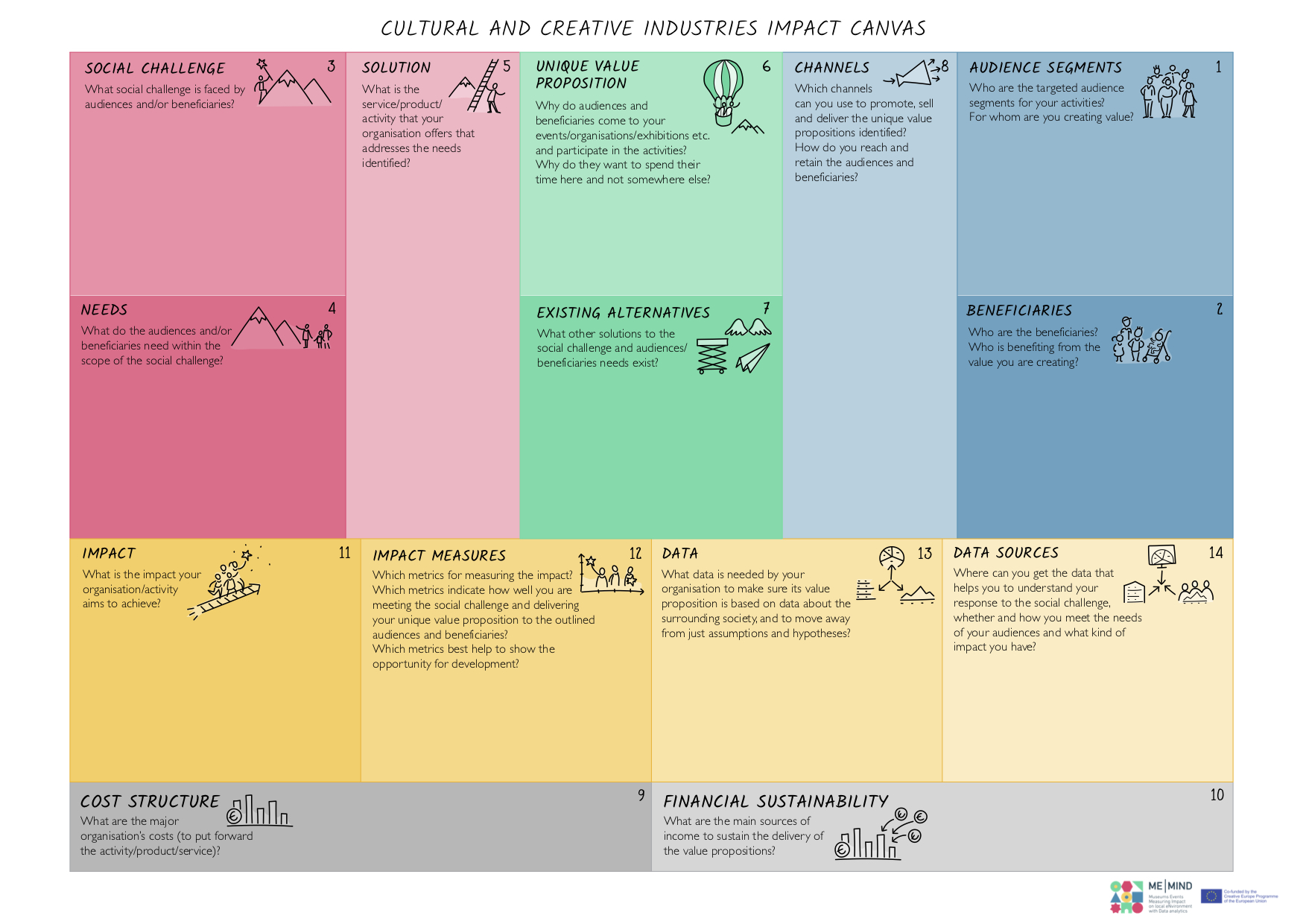

This exhibition demonstrates how we can use cultural environments and events to listen to people and understand how today’s most challenging social issues are perceived by the public. Through the Me-Mind project we want to investigate how we can better explain The role of culture in our society (whether understood as an event, the Internet Festival, or as a museum, the National Estonian Museum) by means of data. Furthermore, we want to share with our stakeholders best practices in order to transform these spaces into a data legacy for future generations.

When we work with culture and data the priority is not what it can do for us today, but how truthfully it will represent us to unknown audiences and future generations.

Axel Gasulla – Co Founder & Head of Research